In much of its history, the Federal Reserve has preferred to use its traditional tools to manipulate interest rates and help to speed up or slow down the economy. Over the last two Fed cycles, the central bank has employed some novel approaches to manipulate long-term interest rates and mortgage rates more directly.

In much of its history, the Federal Reserve has preferred to use its traditional tools to manipulate interest rates and help to speed up or slow down the economy. Over the last two Fed cycles, the central bank has employed some novel approaches to manipulate long-term interest rates and mortgage rates more directly.

Novel monetary policy: QE programs, 2008-2019

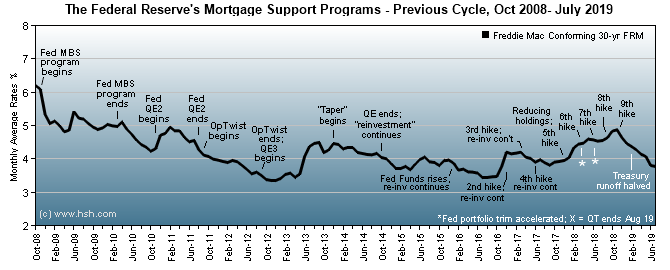

Back in 2008, with financial markets seizing up, the Fed began a then-novel approach to manipulating markets, conducting what it called "Large-Scale Asset Purchases", also known as Quantitative Easing. In varying amounts, and in varying programs of varying size and varying duration, the Fed accumulated a lot of Treasury and mortgage bonds to help keep long-term interest rates low and to keep mortgage and Treasury markets liquid. These programs of course had an effect on mortgage rates and availability while they ran, ensuring there was always a ready buyer (and a buyer at any price or yield) for these instruments even if investors shunned them.

In October 2014, we came to the end of the Fed's first set of Quantitative Easing programs, processes intended to keep long term interest rates low though the purchase of Treasury bonds and to keep mortgage credit flowing at low rates though the purchase of agency-issued Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). It's fair enough to say the programs worked; long-term rates and mortgage rates hit then-record lows in 2012.

At the time these first programs came to a close, purchases of these instruments expanded the Fed's holdings (it's "balance sheet") to about $4.2 trillion. With the process of portfolio expansion complete, the Fed continued to "recycle" money into Treasuries and MBS as cash came in from bonds and mortgages that were paid down, paid off or refinanced. As such, the Fed's "reinvestment" continued to directly influence longer-term market interest rates even after they stopped adding to their holdings.

This original reinvestment process was expected to end when the Fed lifted short-term interest rates at the start of a new upcycle for monetary policy; the first such increase after the Great Recession came in December 2015. At the time, however, the Fed decided to continue its reinvestment policy for several more years, pledging to stop when "normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way." A plan to begin to taper reinvestment to zero in a measured fashion was announced in June 2017, which would take effect later in the year and was expected to have only a minor upward influence on mortgage rates.

The tapering plan began in October 2017, when using inbound funds to purchase of new Treasury bonds was pulled back by $6 billion per month and MBS and agency bonds were trimmed by $4 billion per month. After 3 months (starting January 2018), the $6 billion and $4B reductions turned into $12 billion and $8B respectively; come April 2018, this rose to $18B and $12B and in October 2018 ended up at as $30B in reduction in Treasury holdings and $20B of mortgage-related debt being retired each month.

At its outset, this process was expected to continue for a lengthy but indeterminate period of time, with balances being reduced until the Fed was comfortable that its portfolio trimmed to a size needed only to manage monetary policy.

Only two years into a "runoff" process that was expected to continue for perhaps 3 or 4 if not longer, the Fed changed its plans. At this time, the Fed expected to conduct monetary policy solely using its so-called "administered rates" (federal funds, interest on reserves it holds for banks, etc.), but it would to be doing so in a climate where banks would be holding an "ample supply of reserves". Such reserve holdings meant that the Fed needed to hold a larger-than-expected portfolio in order to ensure that the federal funds target could be maintained in all market conditions. In reducing its holdings, the Fed had been draining funds from the financial system, and financial conditions had begun to tighten more than expected, so it began to wind down the process of disinvestment.

The Fed's program of trimming its holdings of Treasury bonds and mortgage-related holdings remained in full runoff mode until May 2019, with up to $30 billion in Treasuries and $20 billion being retired each month. After that, the Fed began slowing its pace of reduction of Treasury holdings to only $15 billion per month, and this smaller monthly reduction process terminated in September 2019.

Although Treasury reductions were halted, the runoff of mortgage-related holdings continued along at a maximum of $20 billion per month. The Fed prefers to hold only Treasury obligations, but holdings of Treasurys had declined to a less-than-desired level, so the Fed shifted tactics again. In October 2019, the Fed began to use inbound principal payments received from MBS holdings to purchase new Treasuries help rebalance the mix of its holdings.

This was a measured process; redemptions of MBS up to $20 billion per month were used to buy more Treasurys; but any inbound funds in excess of $20B were plowed back into MBS. With mortgage rates rising at the time, refinancing became virtually non-existent in much of 2018 and homebuying became sluggish. As a result, the Fed stopped seeing MBS redemptions above $20 billion.

Although not then meeting their goal to eventually hold only Treasury obligations and no mortgages in its portfolio, the Fed continued to state that it would not be an outright seller of MBS into the open market. However, this thinking began to change in that direction over time, and in its March 20, 2019 release, the Fed noted that "...limited sales of agency MBS might be warranted in the longer run to reduce or eliminate residual holdings. The timing and pace of any sales would be communicated to the public well in advance."

The process of slowly changing MBS holdings into Treasury holdings continued.

Novel Monetary Policy: QE Programs 2020-current

After the Great Recession QE (and other) response programs, the Fed would likely have preferred to never again need to use extraordinary monetary policy responses to prop up financial markets. It would likely have simply let its balance sheet slowly transform itself from a mix of Treasuries and mortgage bonds to one solely comprised of Treasuries over time, and seemed on a long-term path for this to occur.

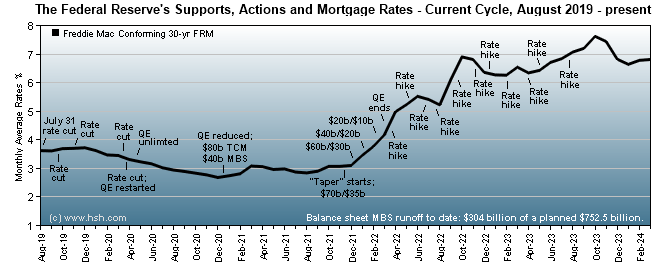

Then, in March 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic hit, the effects of which the world is still dealing with to this day. In short order, economies began to shut down across the globe to deal with the spreading virus; investors panicked, selling everything as fast as they could at any price if a buyer could be found. Financial markets were in a mess and there was a significant chance that a new (and perhaps worse) Great Depression would ensue. At the time, the Fed held about $1.37 trillion in mortgage-related instruments.

To address this market panic, the Fed not only slashed interest rates back to near zero, but also quickly restarted bond-buying programs. On March 15, 2020, the Fed announced that "over coming months the Committee will increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $500 billion and its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion." Such was the panicky state of financial markets that it ran through these sizable amounts in a matter of days, and just eight days later on March 23, the Fed simply stated that "The Federal Reserve will continue to purchase Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning...". In other words, unlimited QE would run until markets calmed.

By June 2020, markets had calmed a bit. At the time, the Fed only noted that "over coming months the Federal Reserve will increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities at least at the current pace." Come December 2020, the Fed returned to specific purchase goals, noting that it would "increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $80 billion per month and agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $40 billion per month."

With U.S. economy healing while the global economy sputtered in fits and starts, bond buys continued at these levels until November 2021, when a "tapering" process was put into place. At the time, it was expected that the Fed would gradually reduce purchases by $10 billion per month for Treasuries and $5 billion for mortgages, so that the wind-down process for accumulating new bonds would take about eight months, after which the first increase in the federal funds rate would occur. Given the experience of the last QE wind-down plan, markets expected to then see a period of portfolio reinvestment of inbound proceeds during a slow rise in short-term policy rates.

This did not occur. With inflation gaining speed and running well above the Fed's hoped-for levels, the central bank accelerated its tapering process to end months earlier than expected, indicating a earlier increase in the federal funds rate. It also surprised investors by revealing that there would be no period of reinvestment, and that balance sheet reductions would begin soon after the federal funds rate started to be increased. The first increase in the federal funds rate for this new cycle came on March 16, 2022.

Outright balance-sheet reductions began in June 2022, first starting with $30 billion per month in Treasury runoff and $17.5 billion in MBS runoff; after three months (September 2022) these figures were be doubled. In his prepared remarks at the time, Fed Chair Powell noted that "For agency mortgage-backed securities, the cap will be $17.5 billion per month for three months and will then increase to $35 billion per month. At the current level of mortgage rates, the actual pace of agency MBS runoff would likely be less than this monthly cap amount." This seemed to imply that outright sales of MBS would be more likely sooner rather than later.

By way of progress toward its goals, as of February 22, 2023, the Fed held $2.620 trillion in mortgage paper, down from a recent peak of $2.740 trillion in April 2022. So far, balance-sheet shrinking isn't happening at the pace the Fed has dictated -- $262.5 billion should have been trimmed from its mortgage holdings by now, but the reduction has only been about $120 billion so far, less than half of what the Fed was shooting for. With 40-year high inflation bringing 20-year high mortgage rates, it's not likely that the Fed will begin any outright sales of MBS holdings very soon, but it's reasonable to think it is being considered.

"Normal" vs. Novel Fed Cycles

So the last cycle was a novel one as the Fed looked to manage its balance sheet while searching for the appropriate level of short-term interest rates to keep the economy running at a measured pace. This new novel cycle will be different than the last and most previous ones, as it also features inflation running at or near 40-year highs.

During "normal" policy cycles, the Fed makes changes to monetary policy by raising or lowering certain interest rates that it directly controls. Traditionally, these include the federal funds and discount rates, but there are also new tools the Fed employs to lift interest rates, too. These include paying banks to keep funds parked with the Fed (called "Interest On Reserve Balances", or IORB) or though a different, more complex method of swapping Fed-held debt for bank cash holdings (called a "Reverse Repo" agreement).

With "liftoff" from zero interest rates nearly a full year ago, and after a short burst of very large increases (and some smaller ones) in the federal funds and other administered interest rates, it's useful to start to consider where Federal Reserve policy might ultimately go in this new novel cycle.

Volume, duration and velocity

Regardless of the tools the Fed uses to get there, interest rates will be elevated over time. The questions are, then, "How much will the Fed lift short-term rates?" (aka "volume"), "How long will it take them to get to their likely peaks?" (aka "duration"), and "How fast will they move them there?" (aka "velocity"). Obviously, for homebuyers, the final question is, "Where will mortgage rates be when higher short-term rates are in place?"

It bears noting that the Fed began its last campaign and started this one in a very unusual position, as nominal interest rates began the cycle near zero in both cases. It also should be noted that the economy seemed to be particularly sensitive to interest-rate changes in the last cycle, so there is a risk of unintended economic damage if the Fed moves rates too fast or too far.

Homeowners, homebuyers and those in the mortgage market remember well the effects on the housing and refinance markets in mid-2013, when a spike in mortgage rates happened in the aftermath of then-Fed Chairman Bernanke's comments suggesting that QE would eventually come to a conclusion (the so-called "taper tantrum"). Starting in May 2013, average 30-year fixed rates rose by more than a full percentage point over a 10-week period.

History may or may not have repeated itself, but an absolute bond-market rout from the end of 2021 into the spring of 2022 lifted mortgage rates by nearly two percentage points this time, and this occurred before the Fed had made much by way of changes to short-term policy rates. As inflation spiked and the Fed kept raising rates in large blocks, mortgage rates moved up to more than 20-year highs late in 2022.

Changes to the downside

It's fair enough to say that history is likely to be a lousy guide to the future, but it's all we have to go on to make judgments. Since the 1980s, there have been 11 Fed cycles for rates, both up and down. There have been periods of pretty pronounced increases, but decreases have been generally larger; for example, a downdraft from 1989-1992 saw a full 6.75 percent chopped off of the federal funds rate as it shrank from 9.75 percent to 3 percent. Other declines of similar size include a 5.875 percent cut from 1983-1986, and more recently, a 5.5 percent slide from 2000-2003. The most recent significant episode was 2006-2008, with a sizable total decline of 5.125, which at the time left rates at historically low levels. The latest decrease cycle was relatively small, totaling a little more than 2 percentage points overall, as rates were pushed back to near zero to help combat the economic effects of the pandemic.

Changes to the upside

So much for the downside of rates. Given that interest rates have generally been declining for 30-plus years since the inflation-fueled days of the early 1980s, the Fed has arguably had some leeway in raising rates, since many of yesterday's "lows" were still elevated by historical standards. Typically, the Fed has exercised somewhat more caution in raising rates when needed, with the largest cumulative increase occurring from 2003 lows to 2006 highs, adding a a total of 4.25 percent to the funds rate. Other smaller cyclical increases of 3.875 percent (1986-1989), 3.25 percent (1982-1983) and a flat 3 percent in 1992-1993 have also been seen. The most recent completed upcycle (2015-2018) featured a total increase of 2.25 percent before rates were again trimmed. The smallest increase of the bunch was just 1.75 percent from a 1998 low to a year 2000 peak during a very short cycle.

Average or typical "volume"

For the last 11 Fed cycles of rates (both up and down) the average cumulative move is 4.125 percent. From the near-zero level where we started this latest cycle of increases, history suggests that when the cycle of raising rates is completed, that this process could leave us with a federal funds rate of about 4.375 percent, all things considered. However, as noted above, the Fed has at times expressed more caution in raising rates than lowering them, or at least limited how far they have gone. In this way, the average upward move for the Fed over the last 11 cycles has been about 3.25 percent, which would leave us with a Funds rate of about 3.375 percent. As we're starting from such a low point, and with it likely that the Fed will want some space to lower rates when the next downcycle begins, we're probably going to see an upcycle for the fed funds rate of perhaps 3.875 percent -- landing us at a nice round 4 percent for the Fed's key policy tool.

We're now fairly well along in the latest upcycle for policy rates. Amid rising and now stubborn inflation, the Fed has added 450 basis points to the federal funds rate since March 2022, and is signaling that there is more yet to come, so this is turning out to be a large volume cycle for the Fed.

Average or typical "duration"

How long will it take the Fed to get us back to a typical or normal level for the fed funds rate? Again, history's not likely to be much of a guide, since the Fed will be responding to changes in inflation and economic growth as they come along. Although this new cycle is starting out differently as the Fed plays a bit of catch-up to inflation (something they haven't faced in many other cycles) the central bank has generally preferred -- absent emergencies -- to make policy changes only at its regular FOMC meetings, held every six weeks or so. At times, it has even preferred a slower pace of increase or decrease, only making changes at meetings where an updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) has been released (once each quarter).

Since March 2022, it has been an every-meeting cadence of increases, and right now it looks as though this will continue for a little longer. After the initial March 16, 2022 increase, the Fed raised rates at meetings in May, June, July, September, November and December 2022 and again in February 2023. There are currently expectations that several additional increases will yet come.

So far in this cycle, the Fed has moved the funds rate back past a "neutral" level (neither lifting growth or damping it) to one that is modestly restrictive and appears on its way to at least a moderately (or even outright) restrictive level. The Fed has recently reduced the size of increases, but has not yet slowed the pace of them. With inflation remaining above desired levels, on-going tightness in labor markets that continues to pressure wages and a resilient overall economy, the Fed has signaled that at least a "couple more" increases of unknown size may yet come.

If the Fed continues to raises rates by 25 basis points at its March and May 2023 meetings, the funds rate would be at a peak of 5.25%; this would match the top of the last strong upcycle for rates. Anything more and the funds rate would be at its highest level in more than 22 years.

The last upcycle for the federal funds rate ran three years before a downcycle began. This upcycle is likely to be of considerably shorter duration -- perhaps half that time or less -- but will feature rather more volume as a result. One feature of this cycle is yet unknown, and will be until it unfolds -- how long rates will remain at or near peak levels once the Fed gets them there.

With inflation still well above desired levels, and policy rates still likely to be moved a bit higher, the volume of this cycle will be greater than has been the case since the 2003-2006 run. That cycle was comprised of a string of quarter-point moves at 17 consecutive meetings; the latest cycle has so far been considerably shorter, the volume of hikes is already greater, but the duration if yet unknown.

Average or typical “velocity”

The most recent iterations of the Federal Reserve policy-setting committees have all shown a preference for small changes in the Federal funds rate, usually a quarter-percentage point at a time, with a few half-point (or more) exceptions, most often on the downside.

However, after more than 20 years of increasing rates by no more than a quarter-point at a time, the Fed used a 50 basis point increase in May 2022, and then went on a four-meeting blitz of 75 basis point increases, backing down to a 50 basis point increase in December 2022 before following that up with a quarter point lift in February 2023.

The Fed's velocity of increases in the funds rate during this cycle is far faster than has been the case in recent Fed history. Even a single 75 basis point increase is uncommonly large, let alone four, and it has been since perhaps the early 1980s when moves of this size were both common and frequent. Large changes to the funds rate are most commonly seen to the downside, usually to address emergencies like the financial market struggles in 2008 or the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Fed has already lifted rates at a speed rarely seen in the last 40+ years, so the velocity of increases for this cycle has been much faster than typical. It appears that the burst of large increases in the funds rate is behind us, but there remains a strong possibility that smaller quarter-point increases will continue and could even be interspersed with half-point hikes, should conditions not change to the Fed's liking.

What will happen to mortgage rates?

Is the history of fairly recent Fed moves any help here at all? Well, the environment in which mortgages are priced today is certainly different than in the past, so the experience taken from those episodes may not be all that helpful. However, the last time we had a federal funds rate at about a "normal" 4 percent rate (either precisely at this rate or rising or falling though it) was in late 2007, and prior to that, November 2005, May 2001 and spring 1994.

The most recent period is arguably most relevant. In late 2007 and early 2008, 30-year fixed mortgage rates slid just below the 6 percent mark, but it is reasonable to say that credit conditions were deteriorating quickly at that point and few investors wanted anything to do with buying mortgages, so that may have kept mortgage rates more elevated than they otherwise might have been.

Still, there was no shunning of mortgages of any means back in 2005, and even though the funds rate was moving in a downward fashion, conforming 30-year fixed rates remained around the 6.25 percent mark, so it may be that this is a "true" or "natural" level for mortgages when the Funds rate is around the 4 percent mark.

Earlier periods are less relevant and certainly provide less comfort. Back in 2001, a 4 percent funds rate was paired with 30-year fixed mortgage rates hanging around 7 percent... and back in 1994, mid-to-upper 8 percent mortgage rates were in play.

The funds rate has been pushed above the 4% level and is expected to be at 5% before long. The last time the funds rate was at 5% was in May 2006. At the time, conforming 30-year fixed-rate mortgages with zero points were averaging about 6.75%, and we'll likely find them there this time around, too.

Interest-rate relief may be hard to find

When fixed mortgage rates rise there will continue to be other options for borrowers, but it may be that borrowers will have to make difficult choices when trying to choose a mortgage. Common Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) will of course be available in the market, and these may provide a lower-cost option for at least some period of time, while holding out the possibility to borrowers for lower rates in the future. Those looking for considerable interest rate relief will probably be disappointed, though, at least if recent comparisons of the last few times we saw 6 percent 30-year fixed rates holds true.

For example, in early 2008, rates for both 30-year fixed and initial rates for 5/1 ARMs were both just under 6 percent. At the time, investors and lenders were generally shunning mortgages, so there was no aggressive pricing by lenders to provide much by way of discounts on ARMs to mortgage shoppers. In fact, investors and lenders were aggressively marketing mortgages of all stripes back in late 2005 and early 2006, a prior episode of 30-year fixed rates climbing above the 6 percent mark. At that time, the interest rate break for selecting a 5/1 ARM was just a third of a percentage point or less, so there was no real rate relief to be found.

With this the case at that time, it's little wonder that borrowers looking to afford homes with fast-rising home prices felt compelled to consider at the lower monthly payments available on interest-only and Option ARMs to enhance affordability.

Puny spreads between the 30-year fixed rate mortgage (FRM) and 5/1 ARM products have existed at other times, too, so borrowers should not expect to always find the roughly three-quarter percentage point (or more) break we see today. In fact, the average break over the last 20 years is a little more than two-thirds of a percentage point (just 0.67 percent).

Initially in this cycle, market-based long-term mortgage rates rose much more quickly than Fed-engineered short-term rates, but ARMs have caught up to a degree. The difference between conforming 30-year FRMs and 5/1 ARMs remains reasonably wide, and for at least a time, a 5/1 ARM may provide valuable rate relief for borrowers who can handle the risks that an ARM presents. It also worth considering that since most ARMs end up on lender books rather than being sold to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac that there can be a large disparity of rates across a local market.

If you're unfamiliar with them, you might have a read through HSH's Guide to Adjustable-Rate Mortgages.

Wrapping it all up

In this latest cycle, it didn't take the Fed very long to get the federal funds rate back to a "normal" level and surpass it. With inflation too high and the economy and labor markets still too strong for the Fed's liking, it may take a while to get us back down to "normal" for the federal funds rate. To be fair, even 6 percent fixed-rate mortgages are still historically quite good but feel very expensive relative to the record-low bottoms and near-bottoms for rates we've become accustomed to during the extraordinary times of the financial crisis, post-"Great Recession" and pandemic era for interest rates. Regardless of whatever nominal level they ultimately achieve, should mortgage rates become to be perceived as "high", we may see the more of the kind of unintended economic damage to housing noted early on in this article. With refinancing all but at a standstill and home sales off 30-40 from recent peaks, we're seeing at least some of it right now.

The future

All in all, if you're thinking of buying a home in 2023 or beyond, it might be a good idea to use a low-to-mid 6 percent interest rate for 30-year fixed rates in your calculations. Thirty-year fixed mortgage rates ran all the way up to 7% in late 2022 before settling back, but persistent price pressures will likely keep them stubbornly high for the foreseeable future.

If you plan on selling a home as mortgage rates are near peak levels, keep in that rising or high interest rates means affordability for buyers gets crimped, especially if there are no viable lower-cost mortgage products for buyers to turn to when loan costs go up. As such, over time you may not have as much pricing power as you do now, or at other times when mortgage rates are lower.

(Image: travellinglight/iStock)

Related articles

- What Moves Mortgage Rates? (The Basics)

- What to do when mortgage rates are rising

- Does the federal funds rate affect mortgage rates?

- Graph: Federal funds vs. prime rate and mortgage rates

Ok bear with me but small town actually happened,. Can banks do only mortgages 36 months that ends then loan ends legally as documents state instead bank calls it extentions to first 36 month loan ends to continue interest changes and that's there mortgage loan you can even get extentions then called extention that adds past due payments extended at claimed end of loan that way you can borrow payment you don't have to stay current. They also stated they don't go by interest from prime lending rate last also don't and won't ever provide amortization on any loans don't know how . Also claimed we put down 10,000.00 when we didn't but loaned money to pay cost to get closing cost and attorney fee loaned they use there own attorney ceo owner last lender did appraisal himself to make value 12,000.00 more to have the 80 20 ratial

Kimberly, I can't follow along but it sounds like you need to contact a real estate attorney for help. Thanks for commenting, Tim Manni, HSH.com