Note: This is a very simplified discussion of a very complex topic. Discussion of the intricate relationships involved, and many important factors (market structures, hedging, advance commitments, and others) haven't been included in the text in order to (hopefully) make it useful to the greatest number of people.

What Moves Mortgage Rates? (The Basics)

The questions are simple enough: What's going on with mortgage rates?

What makes them rise, or fall? Is it the Fed? The economy? Inflation? The banks? The President? Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac? Is it a secret conspiracy?

The answer is that rates are moved by a number of related factors, and believe it or not, you -- Joe or Jane Consumer -- are one of those factors.

Mortgage money can come from many sources, including deposits at banks and brokerages, but most comes from investors through what is collectively known as the "capital markets." This is where investors interested in purchasing certain kinds of debt instruments -- bonds, in this case -- come to buy these items.

In order to attract investors, sellers of bonds must compete with one another to get their money. They do this by offering a variety of "instruments" (also called "product") with differing structures of risk and return over given periods of time. These offerings compete with other investments which are reasonably similar in performance, such as US Treasuries, corporate bonds, foreign bonds, and others.

Who are these investors, and why are they so fickle? Mostly, they're people like you, and you want two opposing things: low payments on your debt, especially your mortgage, and high returns on your investments. You (or your investment advisors or fund managers) will only buy so many low-yielding bonds (mortgage or otherwise), because you'll take your money elsewhere if your returns are too low.

Investor demand for a given kind of investment plays a considerable role in moving market yields, because investors have literally hundreds of places to put their money. It's a crowded marketplace, with many sellers of various product competing for those investor dollars. Investor demand for specific product rises and falls with changes in investment strategies; if demand falls enough, a change needs to be made to attract investors again. How to attract them again? Usually, by raising interest rates.

Of course, it's not as easy or simple as that. Mortgage market makers serve not one client, but two: investors, who want the highest possible return on their investments, and the homeowner or homebuyer, who wants the lowest possible interest rate. Simultaneously, rates need to be high enough to attract investors but low enough to attract borrowers. It's quite a complex dance; investors, though, make the music.

As interest rates (yields) decline, investment customers can become more or less interested, depending upon the direction of economic growth, inflation, appetite for the given product, and several other factors. Typically, though, the lower those rates get, the fewer investors are interested in putting them on their books.

In the case of financial instruments like bonds, things get a little more complicated. Bonds have an interest rate (yield), a dollar amount (face) and a current price (price).

A very simple explanation -- which leaves out a number of very important factors -- would be as follows:

Let's say, for example, that you want to sell a $1,000 (face) bond with a yield of 6%. And let's say that it's a good deal, so ten investors start offering you more than the $1,000 you want. They bid the price up to $1,010 -- $1,020 -- $1,030. In effect, that increase in price is actually borrowing from the interest which the bond will return. Because some of the interest is gone, the actual return to the investor is no longer 6%, but something less than that. When demand for a given bond is strong, prices rise to the seller, and the return to the investor (yield) declines.

Conversely, when demand for a given bond is weak, the price falls. For example, you might have to sell that $1,000 for only $980; and the return to the investor (yield) rises, since the buyer not only gets all the interest on $1,000, but also got a discount on his purchase price.

The principle to remember is this: as a bond price rises, its yield falls, and vice-versa.

Mortgage Relationships to Other Investments

Mortgages are priced for sale to attract investors who seek fixed income investments. There are many kinds of bonds available, and mortgage rates (yields) rise and fall with those competing investments to a greater or lesser degree.

But how to price them? Fixed mortgage rates, like other bonds, track US Treasury bonds quite well. Since Treasury obligations are backed by the "full faith and credit" of the United States, they are the benchmark for many other bonds.

There is no specific "lockstep" relationship between Treasuries of any term and fixed mortgage rates. Given enough data points, a relationship could be established against many different financial instruments. However, as a 30-year fixed rate mortgage rarely lasts longer than about 10 years before being paid off or refinanced, the closest instrument which has similar (though lesser) risks is the ten-year Treasury Constant Maturity. Because of this, the ten-year year Treasury makes an excellent tool to track mortgage rates.

Here's an oversimplification of the relationships of mortgages to Treasuries:

As we mentioned, intermediate term bonds and long-term mortgages (more properly, Mortgage-Backed Securities, or MBS) compete for the same fixed-income investor dollar. Treasury issues are 100% guaranteed to be repaid for an agreed-upon period of time, but mortgages are not; as such, mortgages carry a greater risk of default or early repayment (from refinancing), which could potentially disturb the return on the investment. Therefore, mortgage rates must be priced higher to compensate for that risk.

But how much higher are mortgages priced? In a normal market, the average "spread" or markup above the 100% secured Treasury is about 170 basis points, or 1.7%. That markup -- the spread relationship -- widens and contracts with a range of market conditions, investor appetites and supply of available product -- as well as the presence of competing investment opportunities, like corporate bonds or domestic (or foreign) equity markets. Professional money managers, and investment and retirement funds constantly strive to obtain high-yielding instruments at a given level of risk. Money shuffles from place to place in search of this -- from bond to bond, and market to market.

Related: Learn more about how risks affect the mortgage rate and fees you'll pay

As we mentioned, the relationship isn't a fixed one, but one that changes with market conditions. Recently, for example, ten-year Treasuries rose from 1.60% to 1.90% over a period of a few months -- about 30 basis points, altogether. At the same time, the the average conforming 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose from about 3.65% to 3.74%, a rise of less than 10 basis points. Over time, there are any number of examples where Treasury yields have risen faster than mortgage rates, as well as times when mortgage rates rose faster than Treasury yields. The reverse is also true when rates fall; at times of economic stress, money often flows into Treasuries as a "safe haven", but that's not the case for mortgages, so Treasury yields can drop quickly even as mortgage rates are little affected. A recent example over a few months' time saw the 10-year Treasury yield drop from 1.88% to 0.65% (a record low, and a move of 123 basis points), while the 30-year fixed rate moved only from 3.72% to 3.33%, about one-third as much.

Depending on market conditions, the spread between these two expands and narrows appreciably from time to time, which is why you can't simply take the ten-year yield, add 1.7% to it and know exactly what today's rate is. It goes without saying that these 'spread' relationships vary by mortgage product and also by whether a loan will be held in a lender's portfolio or sold to other entities.

Related: Will today's stock market influence tomorrow's mortgage rates?

An update, in light of more recent market events

All of the above text assumes for the most part that we are in a fairly normal marketplace. It goes without saying that mortgage and bond markets have been far from normal in recent years. First, a short time-line history:

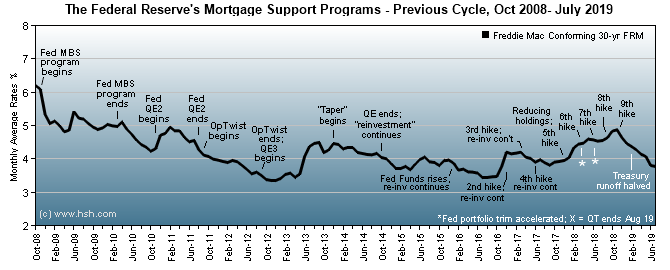

In the midst of the housing market bust and Great Recession, the Federal Reserve took then-unprecedented action and began to buy up Treasuries, bonds issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and Mortgage-Backed Securities. Few investors had any interest at all in mortgages at the time, and without the Fed acting as the lender of last resort, the mortgage market would have come to a complete halt. These so-called Quantitative Easing buys of mortgages propped up the housing market and ultimately totaled $1.25 Trillion.

In sequence, this was followed up by what was called QEII, a second round of supports for the Treasury and mortgage market, which ran for just a short while before giving way to "Operation Twist", where the Fed recycled money created by selling certain short-term debt it held and buying more long term bonds, while also using the proceeds from the mortgages it owned to buy new mortgages.

This lowered both long-term interest rates and mortgage rates for a while, but when the Fed began to run low on short-term holdings to sell, it had to come up with something new.

As such, when Operation Twist came to an end, and with the economy still not fully healed, the Fed began the so-called QE3 program, where they were again directly purchasing both Treasury and Mortgage Bonds to keep rates low and plenty of mortgage money available. This program ended in a gradual tapering of purchases before coming to conclusion in October 2014, but the Fed decided to keep reinvesting inbound proceeds from maturing and refinanced holdings and indicated that they would until "policy normalization is well under way." Reinvestment was the case from October of 2014, but with increases in the federal funds rate in December 2015, December 2016 and March and June of 2017, monetary policy was close enough to normal as to allow the Fed to start to reduce the size of its balance sheet. In June 2017, the Fed announced a program to begin to slowly trim some holdings from its $4.2 trillion portfolio.

To reduce their holdings, the Fed announced that it would reduce its holdings by $6 billion in Treasuries and $4 billion in mortgage debt each month, with only inbound funds in excess of these amounts being used to re-invest in more bond buys. These initial amounts would increase each quarter in like size (to $12 billion after 3 months, then $18, then $24 and finally $30 billion; mortgages would follow as $4, $8, $12, $16 and $20 billion) and the program would run until the Fed felt its balance sheet was back to a manageable size. Analysts thought the Fed would want to retain as much as $2.8 trillion for policy purposes when all is said and done, and the process was expected to take perhaps three years or so and have only a mild effect on mortgage rates, raising them 20 or so basis points than they might otherwise be.

The program ran less than 2 years, and came to a close in September 2019, rather earlier than anticipated, with the Fed was holding investments of about $3.7 Trillion. At that time, the Fed made one more change, and said that in order to gradually change its mix of holdings to 100% Treasuries it would use inbound proceeds from its mortgage holdings to buy only Treasuries.

After 2019, it was expected that the Fed would then remain away from direct manipulation of mortgage markets, preferring to influence economic trends with by moving only the federal funds rate. After years of overt manipulation, we had literally just started to return to mortgage markets largely free of direct government intervention.

The Fed's direct involvement, again

Leaving the market to fend for itself came to an end when financial markets began to seize up as the coronavirus pandemic swept across the globe in February and March 2020, wrecking economies everywhere. Suddenly, the Fed was thrust back into being the lender of last resort again, and in rapid succession moved from not buying bonds at all to offering to buy $500 billion of Treasuries and $200 billion of MBS to calm roiling markets... and promptly ran through those funds in a matter of days. The Fed then announced it would buy up unlimited amounts of both kinds of bonds for the foreseeable future. By December 2020, markets had calmed sufficiently, and the central bank settled on purchasing $80 billion per month of Treasury bonds and $40 billion per month of MBS. This level of bond buying persisted until November of 2021, when the Fed began to "taper" purchases again as inflation failed to act as the Fed expected. This tapering occurred over a five-month period, and the Fed stopped accumulating bonds in March 2022.

The Fed will now swing from Quantitative Easing to Quantitative Tightening and will begin to passively reduce the amount of bonds it holds. Starting in June 2022, the Fed will reduce its holdings of Treasury bonds by $30 billion per month and MBS by $17.5 billion per month. These amounts will double come September to $60 billion and $35 billion respectively, and the Fed may adjust these figures at some later point. While the central bank has indicated it may at some point conduct outright sales of MBS so that it can more quickly return to holding only Treasuries, no plan for sales has been revealed at this point.

The Fed will reduce its holdings by not reinvesting inbound principal payments on the bonds it holds up to the limits noted above; should they occur, redemptions in excess of these caps will be used to buy more bonds. At some point, since it wants to ultimately hold few (or no) MBS, the Fed will likely use MBS proceeds to purchase only Treasuries.

With these actions, the Fed is no longer buying up Treasury debt to help keep long-term rates low and is no longer buying up MBS to help keep the mortgage market liquid. Without this reliable purchaser in the market -- and a buyer that would buy regardless of yield or return -- mortgage rates have risen appreciably as investors adjust to the new market landscape. With inflation high and the Fed taking steps to slow the economy, risks of investing in mortgages have increased, and investors are demanding a greater rate of return to purchase MBS, and with more supply than demand, yields (and mortgage rates) must increase.

We discuss moves by the Federal Reserve and impacts on the economy and mortgage markets at the close of each Fed meeting.

Other Factors

Then, there's the "unknown supply stream", aka "volume". Unlike many other investment opportunities, no one really knows how many mortgages will be originated, then made available for sale (as bonds) in a given period of time. Recently, a quick drop in interest rates produced a large buildup of loans to be sold to investors as homeowners rushed to refinance. This made way too much bond supply available in too short a time, and investors simply couldn't absorb it all at once. Too much supply, not enough demand; prices had to go down, and yields had to go up to attract investors.

Delays, Delays

There's also a time-lag for mortgage pricing. Though shorter than in years past, it takes anywhere from several hours to several days for increases or decreases to get from capital markets to wholesalers to retailers to "the street" where loan originators are working with you.

Not all increases or decreases are passed along, either. Depending upon the size of the change, rates may stay the same (but fees, such as points, may change). Sometimes, a minor increase in bond yields in the morning is followed by a minor decrease in the afternoon, while mortgage rates remain the same all day.

Other Risks

There's also the impact of inflation, which affects both Treasury, mortgage and other fixed-income investments. Rising inflation reduces the actual return on a fixed interest rate investment, so with 2% inflation, that 6% mortgage note returns only 4% "real" interest.

If inflation is expected to decline for the foreseeable future, you can bet that mortgage rates have some room to fall. Conversely, an outlook which suggests higher inflation ahead will see mortgage rates rise, sometimes very quickly.

Also, a poor economic climate affects mortgages much more profoundly than Treasuries. After all, the US government isn't likely to lose its job and suddenly stop making payments, but it's a safe bet that a percentage of homeowners will, even in good economic times.

There's much more to the structure or bond, mortgage and capital markets, including government influences and overseas relationships to our capital markets which can also have an effect, but the above should be enough to give you a modest working knowledge of the market. You'll notice that so far, we didn't mention the Fed at all. Changes to the federal funds rate have no direct effect on fixed rate mortgage pricing, but Fed's their action or inaction (and expectations thereof) can indeed have indirect effects.

The Fed's Traditional Role

Contrary to popular myth, the Fed (more properly, the Federal Reserve) doesn't control mortgage rates. (For more on this, click here.) In fact, their most well-known policy tool -- the Federal Funds rate -- is the overnight interest rate which banks charge each other when a bank needs to borrow money to meet end-of-day reserve requirements. Simply, those rules say that a bank must have so much cash on hand when the books close at the end of the day, and those funds can be borrowed from another bank at this interest rate. You should know that the Fed merely "suggests" what that rate should be, which is why it's called a "target" rate; the actual rate is negotiated between the borrower bank and the lender bank.

A good way to keep a handle on the Fed is to remember that the Fed Funds rate is the shortest of short-term rates -- literally, an overnight loan -- and a fixed-rate mortgage is all the way at the other end of the scale, a loan that lasts as long as 30 years.

From Fed Funds moves, there's a complicated discussion of monetary policy about how Fed moves affect certain deposit and loan markets and inflationary expectations. We'll leave that for another article.

The end result is that the Fed raises or lowers interest rates to help address increases or decreases in economic activity. Lower rates can help banks to make certain kinds of loans more cheaply, especially for business and certain kinds of consumer lending, and that can help to generate greater economic growth. Higher rates can cool demand, helping to keep inflationary pressures from forming.

In some ways, expectations of what the Fed might do can be more important than what the Fed actually does, as their actions or inactions can help to confirm or deny what investors believe.

You may also have noticed that sometimes the Fed cuts interest rates -- and fixed mortgage rates actually rise as a result. Why? If the Fed is taking steps to address economic weakness by lowering rates, that likely means that a return to faster growth -- and possible higher inflation, as well -- is coming sooner, rather than later.

So what moves mortgage rates? Supply. Demand. Competition for money. Inflation. The Economy. Expectations. And you, of course.

We hope that this helps you understand a little better how the whole thing works.

Copyright 2005-2022, HSH® Associates. All rights reserved.

Contact us regarding reproduction of this article.