August 29, 2025

Preface

It's crunch time for the Fed. The central bank seems to be being squeezed on all sides at the moment. Labor conditions seem to have suddenly changed, with a more muted pace of hiring that began earlier this summer. Amid ongoing uncertainty, businesses have turned more cautious in hiring; at the same time, the size of the labor force has been contracting of late, likely from changes to immigration policy, keeping the official unemployment rate at a favorable level. However, the threat of an unwanted worsening in conditions has risen, and Fed Chair Powell noted in a speech in late August that "[...] downside risks to employment are rising. And if those risks materialize, they can do so quickly in the form of sharply higher layoffs and rising unemployment."

Loosening labor conditions give the Fed some leeway if they should desire to lower interest rates. However, the situation is complicated at the moment; inflation is already above the central bank's goal and appears to be starting to move further away from it, and somewhat stronger tariff-led inflation may be lurking in the shadows. While price pressures have been slow to develop, it's not as though they don't exist; what's yet to be seen is where costs are moving once the full panoply of levies is in place, how much of them are passed along to consumers, and how durable any surge in prices may be. How this plays out carries important implications for the direction of longer-term interest rates.

Political pressure on the Fed to cut rates has been considerable, and has only intensified over the last few months. There are also changes in Fed personnel happening, as there is an interim replacement for Fed Governor Kugler, who resigned in August, and potentially another replacement coming, depending upon how the current brouhaha plays out. It is likely that the interim Governor and any other changes will increase the representation of those who have a "dovish" outlook when it comes to changing policy, and who will generally favor lower rates.

That said, Mr. Powell essentially laid the groundwork for a cut in rates at the Fed's September meeting, noting that "risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside," and that the "shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance."

The question is, if the Fed does make a move, what does it mean for mortgage rates this fall?

Recap

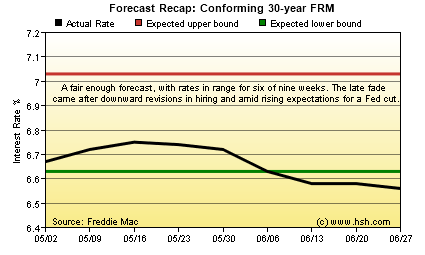

Back in June, we looked out into the summer and expected a relatively stable period for mortgage rates. Tariff-fueled inflation didn't really start to show until later than expected and so had less impact than anticipated during the period. For the forecast period just ended, we expected to see the average offered rate for a conforming 30-year fixed-rate mortgage as reported by Freddie Mac to wander between 7.03% and 6.63%.

Markets produced an actual range over the period was of 6.75% to 6.55%, so rates were generally very stable, spending about two third of the forecast period meandering near the bottom of this range. Thirty-year FRMs only wandered below our forecast bottom after a considerable downward revision to hiring numbers for May and June and a very modest employment report for July. A speech by Fed Chair Powell in mid-August helped them to decline slightly more, as he seemed to pave the way for at least a quarter-point cut in rates at the Fed's next meeting,

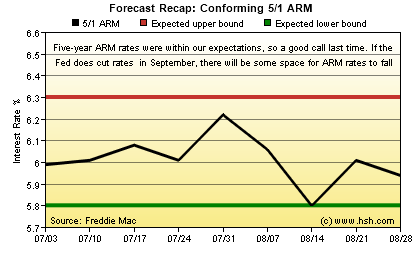

Average offered initial interest rates for 5-year Hybrid ARMs behaved largely as we expected, at least in their usual choppy manner. Two months ago, we thought we would see these initial rates range from 5.80% to 6.30%, exactly the same pair of bookends we used in the prior forecast, and weren't disappointed. Over the nine-week period, the initial rate on hybrid 5-year ARMs got as high as 6.22% and as low as 5.80%, at times providing a viable alternative for homebuyers looking for lower monthly payments.

All in all, the last forecast was pretty solid, even if 30-year FRMs edged below our expected bottom for a time. During what seems to be shaping up to be a transitionary period for interst rates, here's hoping this forecast turns out as good.

Forecast Discussion

In order to more fully address the question we posed above, let's first say that outside of direct purchases of mortgage-backed securities, the Fed does not have any control over mortgage rates. In fact, and outside of direct purchases of Treasury bonds, the Fed has no control over any market-based interest rates. They only have direct control over very short-term interest rates -- the federal funds target rate, the discount window rate and the interest rate paid to banks for parking reserves with the central bank.

Next, let's consider why the Fed might be cutting rates at all. Economic growth over the first six months of this year ran at about a 1.2% pace, half that of the same period in 2024, but seems to be picking up a bit after a difficult start to 2025. For the third quarter so far, GDP is reckoned to be running near a 2% pace -- not stellar, but not a level which should generate concern, and probably one that doesn't need much by way of support to continue to cruise along.

Unemployment remains low, and while hiring has been quite soft, employment levels are near "full". It's not clear that the current moderate level of economic growth needs all that much hiring to keep the unemployment rate fairly stable, especially if the size of the labor force isn't increasing. The Fed's July Beige Book noted that "Hiring remained generally cautious, which many contacts attributed to ongoing economic and policy uncertainty." As the tariff smoke eventually clears, it's certainly possible that hiring activity will start to pick up again. Given that ongoing uncertainty, it's by no means certain that slightly lower short-term rates will spur businesses to start to add to their payrolls at a faster rate.

Core PCE inflation -- the Fed's preferred measure -- has so far been fairly well-behaved, but inflation essentially stopped declining more than a year ago. This measure reached a near-term nadir of 2.6% in April, and has since moved up to a 2.9% rate over the last few months. According to this measure, service costs have mostly leveled out over the last new months but goods prices have turned higher. The core Consumer Price Index (a differently-weighted measure but reflective of many of the same inputs used in PCE calculations) stepped up in July, lifting annualized core CPI to a five-month high, and a second step up and away from the Fed's inflation target. If lowering short-term rates will help lift growth and bolster employment it may make it somewhat more difficult for inflation to settle down again, at least quickly.

Based on the above, it doesn't appear that overall conditions suggest an urgent need for a cut in rates. Mr. Powell described the current stance of policy as "modestly" restrictive, suggesting that it is pretty close to a "neutral" rate, at least in the context of the current environment. A quarter-point cut would likely eliminate most of whatever drag the current level is imparting on the economy, but without rapid deterioration to be seen, the "stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market measures allows us to proceed carefully as we consider changes to our policy stance."

So a quarter-point trim in September it may be. But what about mortgage rates? Last year, when labor conditions looked to be softening, long-term yields an mortgage rates declined considerably, spending the summer on a downward path that took 30-year FRM rates from just under 7% in July to just above 6% by late September. Mr. Powell's 2024 Jackson Hole speech suggesting that a cut in rates was coming soon helped press them down the last quarter point or so, but after the Fed cut rates to address this perceived labor weakness, long-term yields and mortgage rates retraced all of their summer decline in the ensuing months.

At least so far, this year's Jackson Hole speech suggesting a shift in policy hasn't fostered the same effect, and there's been only a modest improvement in rates to be seen. It bears remembering that the Fed taking steps to address emerging issues -- boosting the economy, improving labor conditions -- can often lead to firming long-term rates, not declining ones.

At a time when there are still considerable concerns about the path for inflation, record U.S. bond issuance to finance yawning structural deficits and record high sovereign debt levels, it may be very difficult to get long-term rates to decline very much, at least outside of a real economic downturn. One thing to consider in all of this is if mortgage rates should decline enough help re-ignite a sluggish housing market, who will buy the new mortgage bonds that are created... and at what price?

It's not that mortgage rates cannot fall from here; they can. But the conditions that might support a considerable decline in them just don't seem to be in place at the moment. If labor or other economic conditions begin to turn south quickly, conditions supporting lower rates would return, but for the moment they appear to be at bay. However, even should those conditions emerge, the tempering affect of continuing high debt issuance and still-evident inflation concerns may limit any downside.

Forecast

As we write this forecast, 30-year fixed mortgage rates are already at about 10-month lows, with the most recent modest decline the result of some soft employment numbers. What happens to mortgage rates going forward may very much depend on upcoming labor reports; these include the July JOLTS report, the employment situation report for August, annual benchmark revisions to hiring reports (last year's reset subtracted some 800,000 hires). All these and the August CPI report come before the next Fed meeting.

A quarter-point reduction in the funds rate doesn't mean much. More meaningful is the tenor of the data and any change in the Fed's messaging to suggest if a more pronounced downward path for policy is coming. That will come from the statement, the post-meeting press conference and especially from the updated Summary of Economic Projections, all due on September 17th.

We do think there's at least a little bit of space for rates to decline over the next nine weeks, and are adjusting our expected range accordingly. Over that period of time, we think that the average offered rate for a conforming 30-year fixed-rate mortgage as reported by Freddie Mac will likely wander between 6.35% and 6.80%.

While we've maintained our expected range for hybrid 5/1 ARMs for the last two Two-Month Forecasts, it's likely time to adjust this downward somewhat as well, While not a one-for-one move, any Fed move to lower short-term rates should be at least partially reflected in initial rates for ARMs, as these are more directly influenced by Fed actions. As such, we expect to see the initial rate for a hybrid 5-year ARM as reported by the Mortgage Bankers Association to hold between 5.60% and 6.05% over the next nine weeks.

This forecast expires on October 31, 2025. It's Halloween. In between answering the door and handing out candy, why not stop back in and see if this forecast was a trick or a treat?

Between now and then, interim forecast updates and market commentary can be seen in our weekly MarketTrends newsletter. You can sign up to get MarketTrends by email, too.