There was again no change in the federal funds rate for a fifth consecutive meeting, which is still holding steady at a range of 5.25% to 5.5%. The key policy rate remains at its highest level since late January 2001, and the Fed continued to signal that the next change in rates -- whenever it may come -- will be a downward one.

With the Fed continuing to holding pat, it's reasonably certain that July 2023's increase was the last for this cycle. Fed Chair Powell's prepared remarks indicated that the Fed still "believe[s] that our policy rate is likely at its peak for this tightening cycle."

However, the timing of the first decrease in short-term interest rates is no clearer today than it was yesterday. The Fed again did not give investors what they hoped to hear -- there was no explicit language outlining expectations for lowering rates anytime soon -- and in fact, Fed Chair Powell's prepared remarks again said that "The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent."

As recently as December, the official Fed outlook is that there was a chance of three cuts in interest rates this year. The latest update to the interest rate forecast was essentially unchanged, so the Fed still seems on pace for three interest rate cuts this year. The timing of the three expected reductions could become complicated, as the Fed typically does not prefer to make changes to interest rates close to a presidential election.

At the same time, there's little reason to think at this moment that the Fed will be looking to make cuts at successive meetings, particularly at the start of the new interest rate cycle. With this in mind, and with just six remaining get-togethers this year (and presuming that June brings the first rate cut) that would likely make September and December the other change dates.

To be fair, the economy at the moment doesn't seem to need the additional support that a rate cut will provide. "Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a solid pace," noted the statement that closed the latest meeting for a second consecutive time. GDP growth closed last year with a 3.21% annual rate in the fourth quarter, and the current running estimate for growth in the first quarter of 2024 is 2.1%, so at least closer to a level that might allow inflation to cool further.

It's also true that inflation continues to run at a level pretty far above the Fed's target. However, the Fed continues to point to progress being made on inflation: "Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated," is still the Fed's official position, but inflation reports covering January and February were steps in the wrong direction. Presently, any progress in getting price pressures under control has at best slowed and at worst stalled; but in his post-meeting press conference, Fed Chair Powell that these "bumps" [...]haven't really changed the overall story" for inflation continuing to settle.

Since in the Fed's view there's not yet sufficient evidence that the inflation goal is in sight, let alone getting to it and remaining there, is highly likely that it will another meeting or two before any change in short-term interest rates occurs. If the recent "bumps" in price pressures don't settle back in the next month or two, the prospect remains that the Fed could delay cutting rates into the summer.

Tight labor markets remain are also on the Fed's mind, of course. The statement noted again that "Job gains have moderated since early last year but remain strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low." Mr. Powell's prepared remarks for his press conference noted that "The labor market remains tight, but supply and demand conditions continue to come into better balance." Job openings and voluntary "quits" have trended lower and are closer to pre-pandemic levels, while the unemployment rate remains below 4% and new hires have run at a strong 265,000 over the last three months. Wage growth has steadied lately at about an annual 4.3%, a level that the Fed feels is still inconsistent with core inflation retreating to target very quickly. Recent strong worker productivity gains make these higher wages less worrisome, but there's no way to know if they will persist.

While there was no decrease in short-term rates today, that doesn't mean one won't be appropriate or necessary in the future. In his prepared remarks, Mr. Powell said that "if the economy evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year. The economic outlook is uncertain, however, and we remain highly attentive to inflation risks."

Odds of Fed rate decreases

Per Fed Chair Powell, the Fed now sees policy as "restrictive", that the key policy rate is "likely at its peak for this tightening cycle, and that, if the economy evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year."

With this in mind, the July 2023 increase in the federal funds rate seems to be the last hike for this cycle. Although it may be restrictive, the current level for the federal funds rate may or may not be sufficient to drive inflation back down to the 2% "core PCE goal the central bank has set, or at least do so very quickly. Even absent any additional hikes, this key rate has already remained elevated for a fair period of time but may remain there for perhaps up to a year. This might put the first decrease in rates in the beginning of May, but at this point, June is seen as more likely.

The March 2024 update of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) revealed that Fed members still expect three quarter-point decreases in the federal funds rate by year end, the same forecast as they offered back in December. The median expectation for the level of the federal funds at the end of 2024 is currently 4.6%. However, there was a change in the outlook for 2025; in December, Fed members saw a federal funds target rate of 3.6%, so roughly a forecast of four cuts in rates next year. This has been pulled back to just three cuts for 2025, so even as rates are expected to decline, they will do so more slowly, a bit of "higher rates for longer" expressed in the policy outlook.

The longer-range outlook for rates also was moved up a bit, with a 3.1% funds rate expected at the end of 2026 (up from 2.9%) and a longer-run rate of 2.6% (up from 2.5%). These two-year and beyond outlooks are less forecasts and more speculation, as anything can happen over this kind of time horizon.

While its both hopeful and encouraging for potential borrowers that rates will likely be lower at some point this year, it's also important to temper that enthusiasm. The reality is that even if the three expected cuts do come to pass, a 4.6% median federal funds rate would return it only to about where it ended 2022 and began 2023... and this would still be as high as this rate was back in 2007 -- so moving only from about 22-year highs back down to the equivalent of 16 or 17 year highs. The cost of money will be cheaper, but still by no means cheap.

The March SEP also reflected views that core PCE inflation will be a little bit higher this year than was than expected in December, only falling to 2.6% by years' end (formerly 2.4%). Economic growth is expected to generally be rather stronger this year, with a current forecast of 2.1%, up from 1.4% just three months ago, and the unemployment rate to close the year at a 4% rate. Unemployment somewhere around 4% might be reasonably considered "full employment", which is one of the Fed's mandates.

The next Fed meeting comes in late April into early May. Prior to this meeting, futures markets placed only about a 4% chance that the first cut in rates will come then; post-meeting, this was lifted to about an 8% chance. Investors have significantly changed their expectations for the path of policy over the early months of 2024; by way of example, as recently as the close of the January Fed meeting, 36% of federal funds futures investors were expecting the first cut to come at this [March] meeting. This probability moved to near zero (and actual zero with the meeting now passed) in just six weeks' time. While expectations for a move in June still remain strong -- now about a 68% probability of the first cut coming then -- the incoming data between now and June will have much to say about how much longer the Fed will continue to hold rates steady.

While most likely that the first cut to rates will come in June, we're still of the mind -- and the Fed may be yet, too -- that core inflation will need to at run below the 3% mark for a while before the first rate cut gets serious consideration. Core PCE cracked this level in December and January to reach an annual 2.8%, but a larger-than-expected monthly reading in January (and upward flares in the Consumer and Producer Price Indexes for February) suggest that the improvement in inflation may have slowed or stalled recently.

Fed's "balance sheet" trends

In addition to raising rates, the Fed is continuing the process of "significantly" reducing its balance sheet and is now trying to retire $35 billion of MBS and $60 billion of Treasury debt from its investment portfolio each month. Higher market-engineered mortgage rates over the last year crushed refinancing, slowed mortgage market activity considerably, and softened housing markets appreciably.

Achieving desired levels of portfolio runoff of mortgage holdings may eventually see the Fed need to conduct outright sales of MBS. With mortgage rates high, home sales slow and refinancing at a virtual standstill, the current rate of MBS runoff was and is highly likely to run below desired levels, and has been since the runoff program began 17 months ago.

The general process of balance-sheet reduction is accomplished by no longer using the proceeds of inbound interest and principal payments from the Fed's existing holdings to buy more bonds. As such, reductions in holdings are happening as borrowers whose mortgages make up those MBS pay down their loan balances, which any homeowner knows is a slow process.

As of March 13, the Fed held $2.403 trillion in mortgage paper, down from $2.707 trillion when the QT program began in June 2022, so the reduction isn't happening at the pace the Fed has hoped. By design, some $752.5 billion should have been trimmed from Fed MBS holdings by the end of March, but the decline has only been about $304 billion so far, less than half of what the Fed was hoping to see. MBS holdings will decline faster as mortgage rates decline and refinancing activity picks up. The Fed's present holdings of MBS is at a level they thought would have occurred back in March 2023, so they process is about a year behind schedule.

It's not known (the Fed may not even know at this point) what size the balance sheet will need to be in the Fed's "ample reserves" monetary regime. If we assume that the central bank was comfortable with the size of the balance sheet pre-pandemic, this would be total holdings of about $4 trillion, so they would need to achieve about $5 trillion in reduction over some period of time.

As of March 13, the total Fed balance sheet was about $7.542 trillion, so despite reducing its holdings by more than $1.5 trillion, there remains a ways to go if the goal is to return to a pre-pandemic level. Mr. Powell noted that the Fed has been discussing balance-sheet management, and "the general sense of the Committee is that it will be appropriate to slow the pace of runoff fairly soon, consistent with the plans we previously issued." We would expect that any slowing of reductions would come from the Treasury side, as reductions in the Fed's Mortgage-Backed Securities holdings have already been running well short of goal since the program's inception. We'll likely get an working or even formal outline for these changes after the May meeting.

The Fed's next scheduled meeting comes April 30-May 1, 2024. If a rate cut is to come in June, the Fed will likely tip its hand to the market at the close of the two-day affair. This also means that there's a chance of disappointing investors as well should they choose to kick the rate-cut can further down the road. There is no updates Summary of Economic Projections due, so we'll still be working off the March update at that point.

What is the federal funds rate?

The federal funds rate is an intrabank, overnight lending rate. The Federal Reserve increases or decreases this so-called "target rate" when it wants to cool or spur economic growth.

The last Fed change to this rate came on July 26, 2023 and was the eleventh increase in the funds rate since 2018, when the Fed last completed a cycle of increasing interest rates. The current 5.5% rate is the highest it has been since January 31, 2001.

By the Fed's recent thinking, the long-run "neutral" rate for the federal funds is perhaps 2.5 percent or so, a level well below what has long been considered to be a "normal" level. The Fed has raised the federal funds rate well above this normal level in order to temper inflation pressures that rose to more than 40-year highs in 2022. Once the Fed cycle of increases is complete, short-term rate may be slow to retreat to the Fed's "long-run" 2.5% rate. As of March 2024 2023, the central bank's own forecast doesn't expect for it to return there until 2027 at the very earliest.

The Fed can either establish a range for the federal funds rate, or may express a single value for its key monetary policy tool.

Related content: Federal Funds Rate - Graph and Table of Values

How does the Federal Reserve affect mortgage rates?

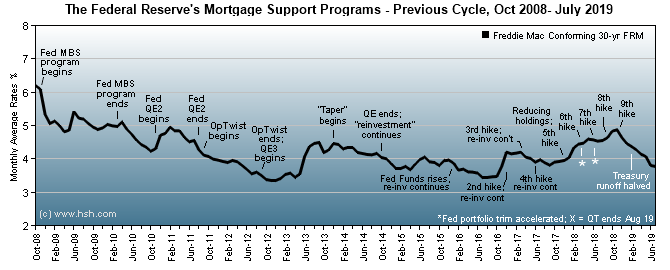

Historically, the Federal Reserve has only had an indirect impact on most mortgage rates, especially fixed-rate mortgages. That changed back in 2008, when the central bank began directly buying Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and financing bonds offered by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This "liquefied" mortgage markets, giving investors a ready place to sell their holdings as needed, helping to drive down mortgage rates.

After the program of MBS and debt accumulation by the Fed ended, they were still "recycling" inbound proceeds from maturing and refinanced mortgages to purchase replacement bonds for a number of years. This kept their holdings level and provided a steady presence in the mortgage market, which helped to keep mortgage rates steady and markets liquid.

This recycling of inbound funds lasted until June 2017, when the Fed announced that the process of reducing its so-called "balance sheet" (holdings of Treasuries and MBS) would start in October 2017. In a gradual process, the Fed in steps reduced the amount of reinvestment it was making until it eventually was actively retiring sizable pieces of its holdings. When the program was announced, the Fed held about $2.46 trillion in Treasuries and about $1.78 trillion in mortgage-related debt. It had been reducing holdings at a set amount and was on a long-run pace of "autopilot" reductions through December 2018.

In 2019, the Fed decided to begin winding down its balance-sheet-reduction program with a termination date of October. With signs of some financial distress showing in financial markets due to a lack of liquidity, the Fed decided to terminate its reduction program two months early.

For that run, the total amount of balance sheet runoff ended up being fairly small, and the Fed was still left with huge investment holdings. At the time, the Fed's balance sheet was comprised of about $2.08 trillion in Treasuries and about $1.52 trillion in mortgage-related debt. Although no longer reducing the size of its portfolio, the Fed began to manipulate its mix of holdings, using inbound proceeds from maturing investments to purchase a range of Treasury securities that roughly mimicked the overall balance of holdings by investors in the public markets.

At the same time, up to $20 billion each month of proceeds from maturing mortgage holdings (mostly from early prepayments due to refinancing) were also to be invested in Treasuries; any redemption over that amount was be used to purchase more agency-backed MBS. Ultimately, the Fed prefers to have a balance sheet comprised solely of Treasuries obligations, and changing the mix of holdings from mortgages to Treasuries as mortgages were repaid was expected to take many years. But these well-considered plans didn't last.

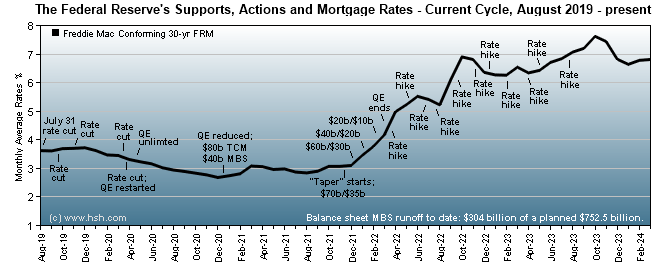

Then came COVID-19. In response to turbulent market conditions from the coronavirus pandemic, the Fed re-started QE-style purchases of Mortgage-Backed Securities in March 2020, so not only did the slow process of converting MBS holdings to Treasuries come to a halt, the Fed was again actively buying up new MBS, growing their mortgage holdings. Through October 2021, MBS purchases were running at a rate of $40 billion per month, and any inbound proceeds from principal repayments existing holdings were being reinvested in additional purchases. As economic conditions settled, MBS bond buys were trimmed to $30 billion per month starting in December 2021 and then to $20 billion per month in January 2022 and it was expected that a similar pace of reduction going forward would occur.

Since the Fed's restart of its MBS purchasing program in March 2020, it had by mid-April 2022 added more than $1.37 trillion of them to its balance sheet. Total holdings of MBS topped out at about $2.740 trillion dollars, and the Fed's mortgage holdings had doubled since March 2020.

The Fed has since concluded its bond-buying program. The start of a "runoff" process to reduce holdings was announced at the close of the May 2022 meeting and began in June 2022 Reductions of $17.5 billion in MBS in the first three months of the program increased to $35 billion per month in September 2022, and desired reductions in holdings remain at this pace today, but market redemptions remain well short of this goal.

What is the effect of the Fed's actions on mortgage rates?

Mortgage interest rates began cycling higher well in advance of the first increase in short-term interest rates. This is not uncommon; inflation running higher than desired in turn lifted expectations that the Fed would lift short-term rates, which in turn has lifted the longer-term rates that influence fixed-rate mortgages. Persistent inflation has reinforced this cycle.

The reverse of the above is also true. Mortgage rates decreased considerably from peak levels, as an improved outlook for price pressures, loosening labor market conditions and cooling economic growth all suggest that the Fed's cycle of increases has done its job, and that before long, lower short-term rates will be coming.

Also important for this new cycle, is that the Fed is no longer directly supporting the mortgage market by purchasing Mortgage-Backed Securities (which helps to keep that market liquid). This means that a reliable buyer of these instruments -- and one that did not care about the level of return on its investment -- has left the market.

This leaves only private investors to buy up new MBS, and these folks care very much about making profits on their holdings. Add in a range of risks to the economy -- including such things as the potential for softening home prices and this may make them more wary of purchasing MBS, even at relatively high yields. With the Fed also no longer purchasing Treasury bonds to help keep longer-term interest rates low, the yields that strongly influence fixed mortgage rates also rose, and may also be slower to decline than they have been in recent years.

What the Fed has to say about the future - how quickly or slowly it intends to raise rates or lower rates this year and beyond - will also determine if mortgage rates will rise or fall, and by how much. At the moment, and given the Fed's new long-term policy framework, the path for future changes in the federal funds rate is of course uncertain, but the current expectation is that the eleven increases in the federal funds rate so far are now less likely to be joined by others yet in the current cycle. As such, the coming Fed interest rate cycle should be one of declining rates over time.

Does a change in the federal funds influence other loan rates?

Although it is an important indicator, the federal funds rate is an interest rate for a very short-term (overnight) loan. This rate does have some influence over a bank's so-called cost of funds, and changes in this cost of funds can translate into higher (or lower) interest rates on both deposits and loans. The effect is most clearly seen in the prices of shorter-term loans, including auto, personal loans and even the initial interest rate on some Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs).

However, a change in the overnight rate generally has little to do with long-term mortgage rates (30-year, 15-year, etc.), which are influenced by other factors. These notably include economic growth and inflation, but also include the whims of investors, too. For more on how mortgage rates are set by the market, see "What moves mortgage rates? (The Basics)."

Does the federal funds rate affect mortgage rates?

Whenever the Fed makes a change to policy, we are asked the question "Does the federal funds rate affect mortgage rates?"

Just to be clear, the short answer is "no," as you can see in the linked chart.

That said, the federal funds rate is raised or lowered by the Fed in response to changing economic conditions, and long-term fixed mortgage rates do of course respond to those conditions, and often well in advance of any change in the funds rate. For example, even though the Fed was still holding the funds rate steady at near zero until March 2022, but fixed mortgage rates rose by better than three quarters of a percentage point in the months the preceded the March 17 increase. Rates increased amid growing economic strength and a increasing concern about broadening and deepening inflation.

A more recent example also shows the converse effect. The Fed last raised rate in July 2023 held them steady through March 2024. Over that time, mortgage rates rose by, and then declined by, more than a full percentage point. All this change in mortgage rates happened while the Fed stood idly by.

What does the federal funds rate directly affect?

When the funds rate does move, it does directly affect certain other financial products. The prime rate tends to move in lock step with the federal funds rate and so affects the rates on certain products like Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs), residential construction loans, some credit cards and things like business loans. All will generally see fairly immediate changes in their offered interest rates, usually of the same size as the change in the prime rate or pretty close to it. For consumers or businesses with outstanding lines of credit or credit cards, the change generally will occur over one to three billing cycles.

The prime rate usually increases or decreases within a day or two of a change in the federal funds rate.

Related content: Fed Funds vs. Prime Rate and Mortgage Rates

After a change to the federal funds rate, how soon will other interest rates rise or fall?

Changes to the fed funds rate can take a long time to work their way fully throughout the economy, with the effects of a change not completely realized for six months or even longer.

Often more important than any single change to the funds rate is how the Federal Reserve characterizes its expectations for the economy and future Fed policy. If the Fed says (or if the market believes) that the Fed will be aggressively lifting rates in the near future, market interest rates will rise more quickly; conversely, if they indicate that a long, flat trajectory for rates is in the offing, mortgage and other loan rates will only rise gradually, if at all. For updates and details about the economy and changes to mortgage rates, read or subscribe to HSH's MarketTrends newsletter.

Can a higher federal funds rate actually cause lower mortgage rates?

Yes. At some point in the cycle, the Federal Reserve will have lifted interest rates to a point where inflation and the economy will be expected to cool. We saw this as recently as 2018; after the ninth increase in the federal funds rate over a little more than a two-year period, economic growth began to stall, inflation pressures waned, and mortgage rates retreated by more than a full percentage point. The most recent episode of declining mortgage rates during the end of 2023 and start of 2024 also demonstrates this point.

As the market starts to anticipate this economic slowing, long-term interest rates may actually start to fall even though the Fed may still be raising short-term rates or holding them steady. Long-term rates fall in anticipation of the beginnings of a cycle of reductions in the fed funds rate, and the cycle comes full circle. For more information on this, Fed policy and how it affects mortgage rates, see our analysis of Federal Reserve Policy and Mortgage Rate Cycles.