HSH.com on the latest move by the Federal Reserve

While there was some dissent among its voting members, the Federal Reserve took no action again today, holding the federal funds rate steady at range of 4.25% to 4.5%. The Fed's quasi-official outlook is still that rates are likely to be lowered before the end of 2025, but the cadence of rate cuts is likely to be irregular and the size of any cuts small.

At this meeting, nine members voted to hold rates steady, while two preferred to cut rates by a quarter of a percentage point at this meeting. The normal group of 12 members was short one for this meeting, but the vast majority preferred to hold steady for a while longer yet.

The Fed been in a wait-and-see mode for the last seven months. Over that time, expectations for significant tariff increases spurred a surge of imports, with this action by businesses and consumers fostering a decline in Gross Domestic Product in the first quarter of this year. We learned this week that the decline was reversed and then some in the second quarter, as GDP growth rebounded from -0.5% to start the year to 2.97% in the most recently completed quarter.

While a more complete tariff picture is starting to come into view, it's by no means a finished picture at this point. Framework deals are in place with the U.K., Japan and the European Union, as well as places such as the Philippines, Vietnam and others. However, there are many deals yet to be completed before the self-imposed August 1 deadline and a framework agreement with China has yet to be hammered out. As such, there is still considerable uncertainty regarding the cumulative effects on inflation, and with the economy still performing fairly, that's enough to allow the Fed to hold for a bit longer yet.

"Inflation remains somewhat elevated," reads the statement that closed the meeting. While we won't get an update on June PCE prices (the Fed's preferred measure) until the day after the meeting closed, the data for May -- literally the first full month after the "Liberation Day" levies were announced -- did show a modest pick up in price pressures, lifting overall PCE inflation to a 2.3% annual rate and core PCE to 2.7%, both up a tenth of a percentage point.

But it's not yesterday's price increases or even today's that the Fed remains concerned about, but rather tomorrow's. The on-again, off-again, kick-it-down-the-road then on-again nature of the implementation of new levies on trading partners makes their outcomes difficult to discern. Moreover, it's not certain how much of any costs increases will be absorbed by businesses, how much may be passed down to the consumer, and how durable any price hikes will be.

It remains a challenging time for the Fed, and not just from a political standpoint. If the modest reversal in inflation (most likely from the impact of tariffs) should continue for June and July, it really cannot cut interest rates to support a slowing economy. Conversely, if the economic impact of higher costs doesn't slow growth all that much (due to offsets that might include, for example, lower energy costs) fair growth at a time of rising costs might instead call for higher interest rates... but the Fed would be reluctant to increase rates, which would generally put pressure on labor market conditions. "We may find ourselves in the challenging scenario in which our dual-mandate goals are in tension," said Fed Chair Powell during his post-meeting press conference back in June.

Fed Chair Powell's prepared remarks reflected continued uncertainty regarding the outlook. "Changes to government policies continue to evolve, and their effects on the economy remain uncertain. Higher tariffs have begun to show through more clearly to prices of some goods, but their overall effects on economic activity and inflation remain to be seen" Regardless, the Fed believes that, "For the time being, we are well positioned to learn more about the likely course of the economy and the evolving balance of risks before adjusting our policy stance."

The so-called "real" federal funds rate (the difference between the core PCE inflation rate and the nominal federal funds rate) is still positive, given that core PCE inflation recently posted a 2.7% annual rate and the funds rate is approximately 4.33%. However, it is by no means clear if the current level for policy is providing or will provide enough drag as to allow inflation to retreat to target levels anytime very soon. The June Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) shows that members are expecting inflation to firm up again over the remainder of the year, so no additional progress on getting inflation back to the Fed's 2% target is expected for some time.

What the Fed said about current risks The statement that closed the meeting didn't set off any alarms, simply saying that "Although swings in net exports continue to affect the data, recent indicators suggest that economic activity has moderated in the first of the year. The unemployment rate remains low, and labor market conditions remain solid. Inflation remains somewhat elevated."

While expectations for future cuts in rates remain, the Fed gave no specific indication that policy will be changed again soon or on any regular basis. "Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains elevated". and "The Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate." noted the statement. Asked about whether the Fed might cut rates or hold in September, Mr. Powell of course didn't provide a direct answer, noting that the data "go in many different directions - the inflation data and employment data - and we're going to make a judgement based on all of the data."

The current Summary of Economic Projection from June suggests that members expect 1 to 2 cuts in rates to happen before 2025 concludes, but the two cuts previously forecast for next year have turned into perhaps only one. This is the case even though growth is expected to turn much more sluggish over the next six months and remain soft next year, and the expected unemployment rate this year and next have been moved up from March's estimation. Despite this less favorable outlook, additional supportive cuts in rates really can't occur if the higher inflation the Committee expects to be in place by later this year comes to pass. The Fed does see a deceleration in price pressures in 2026.

The path back to "neutral"

Still early in a rate-cutting cycle that is likely to take more than two years to complete, it's now clear that the Fed will likely be adjusting policy at a more measured and irregular pace. As it is a moving target and said to not be directly observable, it's not exactly clear where the "neutral" federal funds rate actually is at any given time. Presently, Fed members seem to believe that the long-run neutral rate is around the 3% mark, somewhat higher than was the case leading up to the pandemic. If 3% is the true neutral level for the federal funds rate, there may be perhaps 100 to 125 basis points in reductions before a non-restrictive, non-stimulative "neutral" federal funds target rate is reached. Mr. Powell characterized his opinion of the current stance of policy as "modestly restrictive", and noted that the Fed will "only know the neutral rate by its works," or effect on the economy over time.

The Fed maintains that changes in monetary policy will depend on the incoming data, and that they are prepared to take steps as needed if labor markets or the broad economy stumble. From the statement: "The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals."

Economic conditions leading up to the meeting While GDP growth was negative in the first quarter, this was due nearly solely to a surge in imports to front-run expected price increases. Those effects have faded considerably in the second quarter of 2025, and the preliminary estimate of GDP growth for second stanza is 2.97%, as released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis this morning. The working average for GDP growth for the first six months of 2025 is 1.2%, about half of the pace seen in the first six months of 2024.

The effect on inflation from new tariffs is still largely yet unseen While it is true that progress on getting inflation down to a 2% level has stalled short of the Fed's goal, it's also true that we've not yet seen the kind of increase in overall prices that has been expected to appear. That said, the uneven or even haphazard implementation of the new levies has likely made their impact more of a rolling process than a single event, and so price pressures may take longer to be fully realized or seen across the economy. Core PCE prices did tick up by a tenth of a percentage point in May, lifting the annual rate to 2.7%, and we'll learn of June's inflation on July 31st.

Labor market conditions -- the third leg of this economic equation -- seems to be showing some signs of weakening, but a gradual one. Job openings kicked higher in May and then retreated in June, returning to about the median pace of the first six months of the year. Unemployment eased to 4.1% in June and hiring was at a trend-like 147,000, and initial claims for unemployment benefits have stepped down for six consecutive weeks to their lowest level since mid April. Continuing claims for benefits do remain elevated, signaling that those who are out of work are having more difficulty finding new positions, something that is likely a concern for the Fed.

If there is anything that would see the Fed start to lean toward lowering short-term rates, it would be deterioration in labor market conditions. While less strong than they had been, they are still fair, but likely are starting to be a source of concern.

The June Summary of Economic Projections from Fed members marked down expected economic growth for this year. The first quarter of 2025 posted a final GDP rate of -0.5%, almost solely due to way a pre-tariff surge of imports is handled in the GDP calculation. While these effects have already started to wane, Fed members moved down their forecast of GDP growth this year from a sub-par 1.7% back in March to just a 1.4% annual rate for 2025, a fairly stagnant pace.

Perhaps growth will manage to surprise to the upside, as it has on a number of occasions since the pandemic. Amid an uncertain outlook, the Fed stated that "...recent indicators suggest that growth of economic activity moderated in the first half of the year." Perhaps the rebound in the second quarter will carry some momentum into the latter part of this year, confounding the Fed's expectation of a slowdown.

Odds of Fed rate decreases

Today continued a period of "pause" for the Fed. At present it is not clear how long this pause will be, but there are currently fair odds that the Fed will lower rates at its September meeting.

With the effects of the administration's policies on trade, immigration and spending yet to be fully described or realized, and given the usual ebb and flow of the economy, holding rates steady for now is likely the proper stance for monetary policy. Until some of these effects start to be seen in the "hard" economic data, it will likely remain a time of "wait and see" for the Fed for at least a period of time yet.

The June 2025 update of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) revealed that Fed members expected to be lowering rates this year, but perhaps just a little, with up to two quarter-point decreases in the federal funds rate projected to come by year end. This forecast suggested that the federal funds rate would be at a median 3.9% at the cusp of 2026, only about a half-point lower than present levels..

While it's both hopeful and encouraging for potential borrowers that rates will likely be lower at some point this year, it's also important to temper that enthusiasm. The reality is that even a 4.25% median federal funds rate would only leave it at about where it was in November-December 2022... and this would still be as high as this rate was back in late 2007. As such, this key short-term rate has moved only from about 23-year highs back down to the equivalent of perhaps 17 or 18 year highs. The cost of money will be cheaper, but still by no means cheap.

Perhaps more important for mortgage shoppers to remember is that the Fed does not directly control where mortgage rates go with its normal policy tools. In fact, mortgage rates rose considerably after the Fed began trimming rates last September, and have remained elevated since, for a variety of reasons. Most notably, the Fed has pointed to an increase in the "term premium", where investors demand a higher rate of return to compensate for locking up their money for a longer period of time. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York describes it as such: "The term premium is defined as the compensation that investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond." In essence, investors are asking for better compensation to buy up longer-term debt since the future to them seems highly unsettled.

Just prior to this meeting, futures markets reckoned that there was only slightly more than a 64% chance that a cut of at least a quarter percentage point would come in September. After the meeting closed, this expectation diminished, and only 45% of futures-market contracts now expect a change to come, with 55% expecting the Fed to hold policy steady again. We'll see how these expectations evolve in coming weeks and reference them as needed in our weekly MarketTrends newsletter.

The next Fed meeting comes September 16-17. There will be a fresh update to Fed members' Summary of Economic Projections at that time. By then, we should likely be seeing at least some of the effects of tariff impositions that began in April, as working frameworks for new levies seem to be in place for the U.K., Japan. European Union and several other nations. China still on a kind of "pause", and there are still many deals that need to hashed out before they can all be summed up and their impacts on inflation better assessed.

Fed's "balance sheet" trends

In addition to setting interest-rate policy, the Fed is continuing the process of "significantly" reducing its balance sheet and is trying to retire $35 billion of MBS and $5 billion of Treasury debt from its investment portfolio each month. Since it started, the process of Quantitative Tightening (QT) has slowed from its original pace and will occur over a longer period of time.

Achieving desired levels of portfolio runoff of mortgage holdings may eventually see the Fed need to conduct outright sales of MBS. With mortgage rates high, home sales slow and refinancing at a virtual standstill, the current rate of MBS runoff was and is highly likely to continue to run below desired levels, as has been the case since the reduction program began 38 months ago.

The general process of balance-sheet reduction is accomplished by sequestering the proceeds of inbound interest and principal payments from the Fed's existing holdings instead of buying more MBS. Inbound redemptions to the Fed occur when routine payments are made or mortgages are refinanced. With refinancing activity muted, most of the reductions in holdings are happening as borrowers pay down their loan balances, which any homeowner knows is a slow process.

As of July 23, the Fed held $2.135 trillion in mortgage paper, down from $2.707 trillion when the QT program began in June 2022, so the reduction in MBS holdings isn't happening at the pace the Fed had hoped. By design, some $1.278 trillion should have been trimmed from Fed MBS holdings by the end of this month, but the decline has only been about $572.66 billion to date, far less than half of what the Fed was hoping to achieve. MBS holdings will decline faster as mortgage rates eventually fall and refinancing activity picks up; until then, it's only sales of existing homes and routine mortgage payments that will reduce the Fed's holdings of MBS. The Fed's current mortgage holdings are down to a level they thought would have occurred back in November/December 2023, so the process of reducing MBS holdings is now about 18 months behind schedule.

It's not known (the Fed may not even know at this point) what size the balance sheet will need to be in the Fed's "ample reserves" monetary regime. If we assume that the central bank was comfortable with the size of the balance sheet pre-pandemic, this would be total holdings of about $4 trillion, so they would need to achieve about $5 trillion in reduction over some period of time.

As of July 24, the total Fed balance sheet was about $6.65 trillion, so despite reducing its holdings by about $2.31 trillion, there remains a ways to go if the goal is to return to a pre-pandemic level. Recently, the Fed has slowed its runoff of Treasury holdings to just $5 billion per month, while MBS reductions remain at $35 billion. Redemptions of mortgages have not yet hit this cap since the start of the runoff program, but when they do, any redemptions in excess of $35b will be used to buy up more Treasury bonds rather than more MBS.

What is the federal funds rate?

The federal funds rate is an intrabank, overnight lending rate. The Federal Reserve increases or decreases this so-called "target rate" when it wants to cool or spur economic growth.

The last change to this rate by the Federal Reserve came on December 18, 2024. That was the third decrease in the funds rate since March 2020, when the Fed began an aggressive series of cuts to support the economy as the pandemic upended everything. The current 4.25% to 4.5% range is the lowest it has been since December 2022.

By the Fed's recent thinking, the long-run "neutral" rate for the federal funds is perhaps 3 percent or so, a level well below what was long considered to be a "normal" level. The Fed raised the federal funds rate well above this normal level in order to temper inflation pressures that rose to more than 40-year highs in 2022. While the Fed lowered interest rates fairly rapidly at the start of this new monetary policy cycle, short-term rates may be slow from here to be moved closer to the Fed's "long-run" 3% rate. As of June 2025, the central bank's own forecast doesn't expect for it to return there until perhaps 2028 at the very earliest.

The Fed may establish a range for the federal funds rate or express a single value for this key monetary policy tool.

Related content: Federal Funds Rate - Current and Historical Data, Graph and Table of Values

How does the Federal Reserve affect mortgage rates?

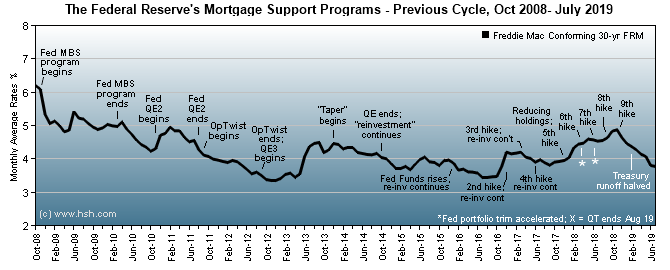

Historically, the Federal Reserve has only had an indirect impact on most mortgage rates, especially fixed-rate mortgages. That changed back in 2008, when the central bank began directly buying Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and financing bonds offered by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. At a time when credit markets has seized up, this "liquefied" mortgage markets, giving investors a ready place to sell their holdings as needed, helping to drive down mortgage rates.

After the program of MBS and debt accumulation by the Fed ended, they were still "recycling" inbound proceeds from maturing and refinanced mortgages to purchase replacement bonds for a number of years. This kept their holdings level and provided a steady presence in the mortgage market, which helped to keep mortgage rates steady and markets liquid for years.

This recycling of inbound funds lasted until June 2017, when the Fed announced that the process of reducing its so-called "balance sheet" (holdings of Treasuries and MBS) would start in October 2017. In a gradual process, the Fed in steps reduced the amount of reinvestment it was making until it eventually was actively retiring sizable pieces of its holdings. When the program was announced, the Fed held about $2.46 trillion in Treasuries and about $1.78 trillion in mortgage-related debt. It had been reducing holdings at a set amount and was on a long-run pace of "autopilot" reductions through December 2018.

By 2019, the Fed decided to begin winding down its balance-sheet-reduction program with a termination date of October. With signs of some distress showing in financial markets due to a lack of liquidity, the Fed decided to terminate its reduction program two months early.

For the original QT cycle, the total amount of runoff ended up being fairly small, and the Fed was still left with huge investment holdings. At the time, the Fed's balance sheet was comprised of about $2.08 trillion in Treasuries and about $1.52 trillion in mortgage-related debt. While no longer reducing the size of its portfolio, the Fed began to manipulate its mix of holdings, using inbound proceeds from maturing investments to purchase a range of Treasury securities that roughly mimicked the overall balance of holdings by investors in the public markets.

At the same time, up to $20 billion each month of proceeds from maturing mortgage holdings (mostly from early prepayments due to refinancing) were also to be invested in Treasuries; any redemption over that amount was be used to purchase more agency-backed MBS. Ultimately, the Fed prefers to have a balance sheet comprised solely of Treasuries obligations, and changing the mix of holdings from mortgages to Treasuries as mortgages were repaid was expected to take many years. But these well-considered plans didn't last.

Along came the pandemic. In response to turbulent market conditions from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed re-started QE-style purchases of Mortgage-Backed Securities in March 2020, so not only did the slow process of converting MBS holdings to Treasuries come to a halt, it was reversed. Through October 2021, MBS purchases ran at a rate of $40 billion per month, and inbound proceeds from principal repayments existing holdings were being reinvested in additional purchases of MBS. As economic conditions settled, MBS bond buys were trimmed to $30 billion per month starting in December 2021 and then to $20 billion per month in January 2022 and it was expected that a similar pace of reduction going forward would occur.

Since the Fed's restart of its MBS purchasing program in March 2020, it had by mid-April 2022 added more than $1.37 trillion of them to its balance sheet. Total holdings of MBS topped out at about $2.740 trillion dollars, so the Fed's mortgage holdings had doubled since March 2020.

The Fed has since concluded its bond-buying program. The start of a new "runoff" process to reduce holdings was began in June 2022. Reductions of $17.5 billion in MBS in the first three months of the program were increased to $35 billion per month in September 2022, and the stated reduction pace remains at this level today, although market redemptions remain well short of this goal.

What is the effect of the Fed's actions on mortgage rates?

Mortgage interest rates often begin cycling higher well in advance of the first increase in short-term interest rates in 2022. This is not uncommon; inflation running higher than desired in turn increased expectations that the Fed would raise short-term rates, which in turn lifted the longer-term rates that influence fixed-rate mortgages. Persistent inflation reinforced that cycle.

The reverse of the above is also true. Prior to the first rate cuts of this cycle, mortgage rates decreased considerably from peak levels, as an improved outlook for price pressures, loosening labor market conditions and cooling economic growth all suggested that the Fed's cycle of increases has done its job, and that lower short-term rates would be coming. While this is likely the case, it doesn't mean that the process will happen quickly or that mortgage rates will decline at a steady pace or even by very much; in fact, mortgage rates and long-term bond yields reversed course and began rising after the Fed started lowering rates to counter emerging softness in labor conditions back in September 2024.

An important condition for this new rate-cutting cycle is that the Fed is no longer directly supporting the mortgage market by purchasing Mortgage-Backed Securities (which helps to keep that market liquid, and rates lower than they would otherwise be). This means that a reliable buyer of these instruments -- and one that did not care about the level of return on its investment -- has left the market.

This leaves only private investors to buy up new MBS, and these folks care very much about making profits on their holdings. Add in a range of risks to the economy -- including such things as the potential for softening home prices and this may make them more wary of purchasing MBS, even at relatively high yields. With the Fed also no longer purchasing Treasury bonds to help keep longer-term interest rates low, the yields that strongly influence fixed mortgage rates also rose, and may also be slower to decline than they have been in recent years.

What the Fed has to say about the future - how quickly or slowly it intends to raise rates or lower rates this year and beyond - will also determine if mortgage rates will rise or fall, and by how much. The path for future changes in the federal funds rate is always uncertain, but the current expectation is that rates will generally be on a downward path over the next few years.

Does a change in the federal funds influence other loan rates?

Although it is an important indicator, the federal funds rate is an interest rate for a very short-term (overnight) loan between banks. This rate does have some influence over a bank's so-called cost of funds, and changes in this cost of funds can translate into higher (or lower) interest rates on both deposits and loans. The effect is most clearly seen in the prices of shorter-term loans, including auto, personal loans and even the initial interest rate on some Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs).

However, a change in the overnight rate generally has little to do with long-term mortgage rates (30-year, 15-year, etc.), which are influenced by other factors. These notably include economic growth and inflation, but also include the whims of investors, too. For more on how mortgage rates are set by the market, see "What moves mortgage rates? (The Basics)."

Does the federal funds rate affect mortgage rates?

Whenever the Fed makes a change to policy, we are asked the question "Does the federal funds rate affect mortgage rates?"

Just to be clear, the short answer is "no," as you can see in the linked chart.

That said, the federal funds rate is raised or lowered by the Fed in response to changing economic conditions, and long-term fixed mortgage rates do of course respond to those conditions, and often well in advance of any change in the funds rate. For example, even though the Fed was still holding the funds rate steady at near zero until March 2022, fixed mortgage rates rose by better than three quarters of a percentage point in the months that preceded the March 17 increase. Rates increased amid growing economic strength and a increasing concern about broadening inflation pressures.

A more recent example also shows the converse effect. The Fed last raised rates in July 2023 held them steady through August 2024. Over that time, mortgage rates rose and then declined by well more than a full percentage point. All this change in mortgage rates happened while the Fed stood idly by.

What does the federal funds rate directly affect?

When the funds rate does move, it does directly affect certain other financial products. The prime rate tends to move in lock step with the federal funds rate and so affects the rates on certain products like Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs), residential construction loans, some credit cards and things like business loans. All will generally see fairly immediate changes in their offered interest rates, usually of the same size as the change in the prime rate or pretty close to it. For consumers or businesses with outstanding lines of credit or credit cards, the change generally will occur over one to three billing cycles.

The prime rate usually increases or decreases within a day or two of a change in the federal funds rate.

Related content: Fed Funds vs. Prime Rate and Mortgage Rates

After a change to the federal funds rate, how soon will other interest rates rise or fall?

Changes to the fed funds rate can take a long time to work their way fully throughout the economy, with the effects of a change not completely realized for six months or even longer.

Often more important than any single change to the funds rate is how the Federal Reserve characterizes its expectations for the economy and future Fed policy. If the Fed says (or if the market believes) that the Fed will be aggressively lifting rates in the near future, market interest rates will rise more quickly; conversely, if they indicate that a long, flat trajectory for rates is in the offing, mortgage and other loan rates will only rise gradually, if at all. For updates and details about the economy and changes to mortgage rates, read or subscribe to HSH's MarketTrends newsletter.

Can a higher federal funds rate actually cause lower mortgage rates?

Yes. At some point in a cycle, the Federal Reserve will have lifted interest rates to a point where inflation and the economy will be expected to cool. We saw this as recently as 2023; after the eleventh increase in the federal funds rate in over a little more than a 16-month period, economic growth slowed, labor markets cooled, inflation pressures waned and mortgage rates retreated from multi-decade highs, falling by more than a percentage point and a half from peak levels by the time the Fed cut rates in September 2024.

The most recent episode of declining mortgage rates during the end of 2023 and start of 2024 also demonstrates this point.

As the market starts to anticipate this economic slowing, long-term interest rates may actually start to fall even though the Fed may still be raising short-term rates or holding them steady. Long-term rates fall in anticipation of the beginnings of a cycle of reductions in the fed funds rate, and the cycle comes full circle. For more information on this, Fed policy and how it affects mortgage rates, see our analysis of Federal Reserve Policy and Mortgage Rate Cycles.